Focus on the main priorities in Italy: Health, school, work, digitalisation

On the government crisis and the real needs of Italian citizens

The reckless government crisis in the midst of the pandemic, which seemed to have been overcome only a week ago after the vote of confidence, was formally opened on 26 January with the resignation presented by Prime Minister Conte to the President of the Republic. For us at DiEM25, the priorities remain those that weigh most heavily on the lives of citizens; they are the ones that should mobilise the country’s resources, energies and intelligence. But currently, many are discouraged by the lack of farsightedness and responsibility of politics towards the gravity of the situation.

Health

We are still in the midst of a pandemic. Nevertheless, Italy — compared to other countries in Europe — has started well in its vaccination campaign, maintaining a good number of daily administrations, which has placed it at the top places in Europe. However, it has recently suffered the slowdown imposed by Pfizer.

As Italian citizens, we absolutely cannot afford to let our guard down when it comes to our health. An even greater effort has been required of our doctors, nurses and all healthcare staff on a daily basis (it is they who carry the greatest emotional burden and human fatigue). We are all tired of intermittent restrictions, of rules that do not allow us to have the kind of human and social close and friendly relations for which we, Italians in particular, are known for and which we cannot do without. But breaking from COVID-19 measures now as suggested by right wing forces would jeopardise all the work done so far.

All front-line staff should be granted a one-off bonus in order to show gratitude and appreciation for their exceptional effort against this terrible pandemic. But this is not enough, the government also needs to ensure the prospect of stable recruitment, which can put an end to the precariousness created by cuts to public health, which — according to the Gimbe Report — have resulted in the defunding of the National Health Service to the tune of €37 billion in the decade 2010-2019.

However, it should be emphasised that the priority focus on public health does not in any way support Renzi’s axiom of the need to use the pandemic crisis support of the European Stability Mechanism. This is essentially for three reasons. Firstly, being the only European country to activate such a mechanism, we would risk paying for it in terms of a “stigma” effect through the inflexible “market discipline”, as soon as the ECB were to abandon its accommodating policies and return to the “capital key” rule. Secondly, the strong conditionalities of the ESM are provided for by its statute, which has not changed. Thirdly, investments in public health — many studies have shown this — have a positive impact in terms of lower future spending in health as well as in collective welfare, offsetting over time the burden on public finances. Ultimately, we do not know whether the 19.7 billion allocated to health in the second draft of the “Next Generation Italy” is sufficient, but we do know that it is a necessary reversal of course compared to the past, from which territorial health and personnel must benefit.

School

Although, much has been done, there is still a lot more to do, and it could be done in a much better way. Now, it is time to join forces and concentrate on solving a number of problems to ensure that all students return to class, which, at least for this year, will be affected by COVID-19 measures. Therefore, several actions must be taken, such as:

- Upgrading the connectivity of all schools

- Renovating and making school spaces healthy in order to reduce ‘henhouse classes’

- Retrofitting for energy efficiency school building

- Wiring all school buildings to improve connectivity

- Hiring teachers and making schools more energy efficient

- Encouraging active teaching that is open to the local territory, promoting cultural extracurricular activities that strengthen the link between school and citizenship

These are all investments that would remain with the schools and the communities they belong to, even after the pandemic.

In addition, transportation needs to be improved and a 100% secure back-to-class plan needs to be devised as soon as the course of the virus allows. Such measures would be a form of compensation for all the students who have been left behind in recent months and for the normality taken from the lives of so many young people. Not making the mistake of non-priority expenditures (such as the purchase of rolling desks) is the least we can promise to our children. The 27.9 billion for “Education and research” — one of the six missions of “Next Generation Italy” in the second draft — should be properly invested for the benefit of future generations, especially for the component intended for “strengthening the skills and the right to study.

Work

The pandemic and the measures put into place have left many atypical, intermittent and informal workers in this country without protection. By March, we risk more than a million newly unemployed people, as well as business closures and bankruptcies. It will take years to bring Italy back in balance, and this can only happen with a huge flow of public investment to ensure that the recovery is neither too slow nor too delayed.

The second draft of the “Next Generation Italy” allocates a total of 6.7 billion euro to ‘labour policies’, within the mission called ‘Inclusion and Cohesion’. This is perhaps not enough to repair a female employment rate shamefully far from the European average and an unemployment rate, especially among young people, that is too high — weighed down by the year-on-year decrease in employment (- 390 k) and the increase in NEET (+479 k)s, equal to -869 thousand units, according to the latest ISTAT press release.

Digitalisation

Digitalisation: together with ecological transition, it is one of the main strategic priorities of policies agreed at European level. The allocation for digitalisation — of the Public Administration and the production system respectively — is 11.3 billion and 26.6 billion in Next Generation Italy. This is a mountain of money. It will therefore be crucial to allocate these resources to projects that are actually useful for the country’s development.

This crisis has increased social and territorial inequalities; the gap between the two is likely to be ever wider. We can already see how the gap is huge in the south in terms of beds, vaccines available per region and per capita public spending on businesses and families. Digitalisation will therefore increasingly become one of the key words to monitor and control the quality of spending and to stimulate local authorities to carry out their programmes, through the transparent tracking of public spending.

There is a huge amount of work to be done, and we are already starting out weakened by a policy that does not seem up to the severity of the current crisis. But as Brian Eno — member of the DiEM25 Advisory Panel — said, ‘even if there is no recipe, it is important to start cooking, only then will the dish take shape’.

This piece was authored by Patrizia Pozzo, a member of the DiEM25 Coordination Collective, and Antonella Trocino, a member of the DiEM25 National Collective.

Photo Source: Photo by Antonella Trocino.

Did we see something like Another Now’s Crowdshorters in action?

You be the judge!

In my Another Now I imagined a new type of resistance movement that uses the tools of finance to bring down capitalism and create a democratic market socialist economy in its stead. I called them Crowdshorters. I received many messages suggesting that the Crowdshorters are emerging for real, with the Reddit group that supported GameStop kickstarting the movement.

Is there a smidgeon of truth in this? Judge for yourselves. Look at this Financial Times piece, or this Guardian article, and then read the following extract from Another Now. I can’t wait for your reactions…

Extract from Another Now’s Chapter 4: ‘How Capitalism Died’

…In the Other Now, the Ossify Wall Street movement, as it was known, sprang up in New York City just as Occupy Wall Street had in Our Now. However, over there it went global under the name Ossify Capitalism, or OC for short. At the time Costa had been excited by Occupy Wall Street and its various equivalents worldwide: the Indignados in Spain, who in their tens of thousands took over the plazas of the main Spanish cities; the Greek Aganaktismenoi, who made Syntagma Square their own for three joyous months in the spring of 2011; the Nuit Debut gatherings a few years later in Paris. Alas, that early promise fizzled out as fast as it materialized — especially after the surrender of the Obama administration to Wall Street in early 2009 and of the Greek leftist government to the oligarchy-without-frontiers in the summer of 2015. The great difference between the two movements was that the OC rebels recognized the futility of occupying spaces — squares, streets or buildings.

‘Capitalism does not live in space but in time and in the ebb and flow of financial transactions,’ was how Esmeralda, one of its impromptu leaders, put it. The team she led was known as the Crowdshorters. According to Kosti, it was the first group to demonstrate the vulnerability of financialized capitalism and the power of a well targeted digital rebellion. Its first success came when it took direct aim at the financial instruments of mass destruction that played such an important role in causing the 2008 global crash: collateralized debt obligations.

These CDOs were a form of synthetic debt with which Eva would have been intimately familiar, having played a part in their manufacture while at Lehman. They can be imagined as boxes in which their creator places many tiny chunks of debt: a few pounds of the mortgage owed by Jill to her local bank, a few yen owed by Toyota to a Japanese pension fund, a few euros owed by a Greek bank to a German one, a few dollars owed by the US Federal Government to JP Morgan, and so on. Each CDO was filled with countless chunks of different types of debt, each with its own risk of default and interest rate.

The great selling point of CDOs was the fiction that they were a safe bet. Since they contained so many different pieces of debt owed by such a diversity of people and organizations, buyers were told that there was no chance that more than a few of those chunks would turn sour at once. Moreover, each CDO was so complex it was impossible for any human, even its creator, to estimate its value, so there was no real limit to what it could sell for: those who created, sold and traded in CDOs simply let the market decide, and no one in the market could argue that they knew any better. They were an invention worthy of a Bond villain, the ideal snake oil: pieces of paper that were, at once, completely opaque and yet apparently safe and lucrative. The false sense of security they offered led to far higher demand — and far higher prices — than CDO creators expected. Observing bankers’ surprise at the high prices, others flocked in to place their orders, boosting prices ever higher.

With so much money being made, the bankers who had created the CDOs soon forgot their original purpose: to offload bad debt onto gullible victims. Unable to stand by as others profited from their creations, bankers like Lehman lost their faculties and began to buy back their CDOs. The more they bought, the higher the already stratospheric prices went, the greater the paper value of their stacks of CDOs, and the larger their bonuses. Delirious with their profits, the bankers borrowed mountains of money from each other to buy even more CDOs.

In short, the bankers fell headlong into their own trap. And when all of the bad debts inside those CDOs turned sour and the bottom fell out of the market in 2008, the financiers fell into a bottomless pit of their own making. As they sank, the politicians and the major central banks — the Fed, the Bank of England, the ECB and all the rest — rushed in to re-float them. That’s when Esmeralda’s Crowdshorters struck.

Techno-rebels

Esmeralda, like Eva, had worked for one of the large financial houses until just before the crash, and thus understood their inner workings well. Using her expertise, her Crowdshorters undermined the central banks’ efforts surgically and stylishly. They realized what few understood: by privatizing everything, capitalism had made itself supremely vulnerable to financial guerrilla attacks. Specifically, Esmeralda recognized that the creation of CDOs out of plain debt — a process known hubristically and ironically as securitization — afforded the perfect opportunity for a peaceful grassroots revolution.

in Croydon or small businesses in Preston was owed to some private corporation. However, the corporation had pre-sold these payments ages before to some financier. What exactly had the financier bought? The right to collect the future revenue streams from the little people. And what did the financier do with that right? Sliced it up into tiny chunks and placed them in different CDOs, which in turn were sold on to other financiers — globally!

Esmeralda and her comrades had the technical skills to unpick the contents of every CDO. Painstakingly, they wrote software that could identify precisely which chunk of debt within each CDO was owed by which household, when each chunk of a bill or a debt repayment was due, to whom it was owed, and who owned the specific CDO at every point in time. Using this vast database of information, they were then able to contact households — most of which were outraged by the bankers’ behaviour and the bailouts they were set to receive — and invite them to participate in low-cost, targeted, short-term payment strikes — or crowdshorting as Esmeralda called these campaigns.

The Crowdshorters’ pitch to residents was simple. In fact, one of the first of them — a circular sent by Esmeralda to Yorkshire residents — is now commemorated in the Other Now on a plaque that adorns the Houses of Parliament in London:

Help us bring down those profiting from your exorbitant water bill while you are struggling to put food on the table. just delay paying your water bill for two months, and don’t worry about the late payment fee. we are crowdsourcing funds to compensate you. united we stand, divided we fall!

Similar plaques are on display in the entrance to the Capitol building in Washington DC, even the Greek parliament on Syntagma Square. The uptake was breathtaking. People all over the UK, soon the world, began to take great pleasure in tracking, and heeding, the Crowdshorters’ calls. Their meticulously coordinated payment strikes caused cascades of crashes in the CDO market which spilled over into the major stock exchanges. Within three weeks, the central banks realized it would be impossible to re-float the bankers’ trillions of dollars’ worth of securitized debt while, at the same time, the privatized utilities were going bust and demanding bailouts too.

Unable to convince Congress to pump the missing trillions into Wall Street for a second and then a third time in the space of a few months, the US Federal Government had to allow Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and the other behemoths to be wound down. The repercussions were immense. Europe’s banks, which were in a far worse state than America’s, shut up shop too. The City of London was in meltdown. Governments were forced to nationalize the failing utilities. The Fed, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, even the People’s Bank of China, had no alternative but to step into the void and provide citizens with bank accounts – the first stirrings of PerCap.

While they played a central role in sinking global finance, Esmeralda and her Crowdshorters could not have sparked the OC revolution on their own. Wrecking an already collapsing Wall Street was one thing; ossifying capitalism was quite another. This is where other techno-rebels came into the picture.

Recognizing pension funds as the largest shareholders in the great corporations, a band of radicalized traders working out of Mumbai’s financial centre and calling themselves Solidarity Sourcing Proxies — Solsourcers for short — decided it was time to target globalization’s most ludicrous racket. Drawing inspiration from the Crowdshorters, the Solsourcers invited people to nominate companies with the worst record of zero-hours contracts, low pay, carbon footprints, working conditions and the tendency to ‘downsize’ in order to boost their share prices. Millions of people from all over the world pitched in to name the worst offenders. Then the Solsourcers organized the mass withholding of pension contributions to the pension funds that owned shares in those companies. The mere rumour that the Solsourcers had targeted a particular pension fund turned out to be enough to send its shares crashing and to cause an exodus of worried investors from equity funds related to it. The Solsourcers eventually needed only to send to a pension fund a list of the companies it wanted it to divest from, and the fund would do so immediately, lest its incoming pension contributions dried up.

Realizing their power, the Solsourcers spread their wings globally and began to make more ambitious and highly sophisticated demands, not merely for divestment from unscrupulous employers and environment-destroying corporations, but for reforms to corporate law. Inspired by a flat management structure pioneered by a corporation based near Seattle, they managed to take the first steps towards prescribing by law the corporate model one person one share one vote.

By early 2010, the Solsourcers had been joined by another group of techno-rebels. Calling themselves Bladerunners in homage to Rick Deckard, the fictional character whose job in a famous 1982 sci-fi movie was to hunt down and kill androids, they thought of themselves as neo-Luddites, even choosing as their patron figure Lord Byron, the poet laureate of the original Luddite movement…

Photo Source: Mike Mozart on Flickr.

Free vaccines for everyone

DiEM25 on how to do this, now!

People are dying by the thousands each day, thousands of companies are filing for bankruptcy, and millions of people are languishing under draconian lockdown measures. At the same time, vaccination centres are held back due to a shortfall in vaccine supplies.

The EU’s vaccine procurement program has proven to be an expensive fiasco. To preserve the Franco-German axis, they ordered 300 million doses from a French company that produced none and too few from the German company that exported most of its vaccine output so far to the UK, Israel, the USA etc. Recently, the two main companies that can supply the much-needed vaccines announced new cuts to deliveries to EU countries.

This fiasco, and the lives we shall lose unnecessarily, raises the political question: What should be done now to limit the human and economic cost of the EU’s latest motivated failure? Two problems need to be solved: Where will the money come from to ensure that free vaccines are available to everyone? And, what to do about Big Pharma, a handful of multinational companies that hold whole populations to ransom?

Who should pay?

Central banks are printing mountains of money which they pass on to the banks which, in turn, pump it into large corporations that use the money to buy back their shares and thus boost their paper value (and, of course, their directors’ pay). Since the pandemic began, the European Central Bank has printed 1,700 billion euros for that purpose. Therefore, the answer is clear:

The European Council should immediately order the European Central Bank to pay whatever sums are necessary to purchase all the doses of the vaccine Europeans need, plus another equal quantity to be sent, free of charge, to low income countries.

In summary, using the considerable monetary power of the ECB, the cost of speeding up production and distribution of vaccines can be covered immediately and fairly. Moreover, it is our duty as Europeans to use this power to deliver to low income countries, lacking similar power, the vaccines their people need — and thus to lead other rich economic blocks by example.

What to do about Big Pharma?

The medical-industrial complex represents a clear and present danger to European citizens. They use the resources provided by our states (e.g. direct research funding and all the accumulated knowledge of scientists educated by the states) to produce medicines and vaccines that they then monopolise through patents — which prove especially lucrative during emergencies like the current pandemic. Taxing and regulating them is important but not enough. The central issue is property rights over their patents. Challenging these can only be part of a challenge of capitalism’s most basic tenets.

In the context of DiEM25’s Post-Capitalist drive, DiEM25 campaigns for a change in corporate law so that citizens, represented by the EU, acquire shares in pharmaceutical companies operating in the EU so as to benefit directly, as co-owners, from our public research and funding programs.

Only when property rights over patents are socialised will public health become viable.

The time to act is now!

Only through a large-scale intensification of COVID-19 vaccine production will inoculation programs run at full capacity, thus preventing an even greater economic and humanitarian crisis both in Europe and worldwide.

DiEM25 demands that the European Council gives the green light to its institutions, the European Central Bank above all else, to spend whatever it takes to end the pandemic. Moreover, we call upon European progressives to join us in a campaign to transform property rights over life-saving vaccines and medicines.

The Left is failing because of a lack of understanding of how diverse revolutionary subjects are

To seize the moment, we must understand the ways in which various forms of oppression intersect

This article is a response to “Why Identity politics is killing the left” as an underrepresented, marginalized, and vulnerable person in male-led movements. Equal or diverse representation in movements does not automatically assure the equal ability or capacity to participate and decide.

The recent piece on “Why Identity Politics is Killing the Left” brought up two topics: (1) how symbols do not change the material conditions of people, and (2) identity politics, but failed to argue or nuance any further. This is problematic as the article’s title directly blames identity politics as the demise of the Left without any added thought.

Signs and symbols albeit “empty” are not useless

Throwing away signs and symbols and calling them “empty” completely disregards and erases what our comrades and allies in the USA, specifically black, and LGBTQ+ grassroots movements, and people all over the world have contributed to the struggle to ensure political positions and strategies that help us all. Lest we forget, without the symbolic empowerment through Trump, white supremacy and fascism in the USA would not have grown the way it did. The symbolism surrounding Trump and “Trumpism” led to the horrific current events in the US, most recently the storming of the Capitol, and has also spread all over the world such as in Japan, India, and other places in between.

Sans the lack of nuance in the original piece, I argue that there is value in the “empty” symbolic significance of having, even just in itself, a woman in a position of power, a BIPOC in decision-making spaces, an LGBTQ+ person up on podiums, or people with different abilities or are neurodivergent delivering key speeches. This is a reality that privileged members of society, especially cis-heterosexual (white, able-bodied, neurotypical, or passing as any or all of these) men, do not realize when they have been represented in every space and medium all of their lives. Representation and symbols matter a lot to those who hardly ever get represented because the reality that more than half of the world are not cis-heterosexual men isn’t reflected at all anywhere else.

Saying that empty symbols are useless doesn’t problematise how we define symbols and the lenses we use to inform ourselves. For example, we do not throw out democracy because of how it has become more about electoral politics, but we consciously struggle to define and redefine these “symbols” and means to reflect a world that is rooted in justice and equity.

Global struggle

Movements have shifted from not only locally organised groups to a larger network of unity all around the world towards a global struggle for justice and change. This was brought about by various forms of oppression that have continuously been expanding their machinery and reach. This has been done in ways that are more insidious than before and deeply seating itself exposing the centuries, and even millennia-old systems that afforded it its place in humanity’s history.

The protests and boycott against Amazon is an example of the wide reach and different expressions of oppression not tied to class alone. This can be analyzed through the distinctions of intersectional issues. We cannot with any conviction truly say that the experiences of workers and small business owners in India and all over the world who joined the (#MakeAmazonPay) protests of workers in America have similar conditions and experiences of oppression. Just because people gathered under one banner does not erase their intersectional issues because it is precisely in these differences that alliances are needed in the forefront to lead the struggle.

Movements that were mostly class informed have always been heavily intertwined with race and gender, while other differentiations that have left the rest behind in the struggle are continuously being uncovered as we fight for our place in the world, and even at the “class only” table. In the absence of sharing that space which we have equally contributed to, and carried on our backs, we create our own.

The lack of understanding of how diverse the revolutionary subjects are is what made the Left fail

In the sincerity and empathy towards fighting for justice and change, we align ourselves to help and inform each other to be stronger and better as the enemy has continuously transformed itself as well. Spaces for dialogue, collaboration, albeit the obvious non-homogeneity of any group of people, are spaces to maturely, transparently, and responsibly hold each of us accountable to each other. The lack of shared violent experiences and generations of trauma and oppression should not be a problem when empathy and sincerity towards addressing these issues are at the core of the movement, and not fighting over power.

If we fail to acknowledge developments in social theory, we will not be able to explain how workers are oppressed in the 21st century where material work in many areas of the economy is not there anymore. And in as much as many agree that we should not be oppressed on the basis of our sex, gender, race, abilities, neurodiversity, the blindness to our own potential sexism, misogyny, racism, ableism, and the like, supersedes the actual work that needs to be done to remove these oppressions that the rest of their allies face.

Identity politics and intersectional feminism moves us forward

In order to understand and remain politically relevant in the struggle, one must realise that the intersections of oppressions are important to bring forward, and seize the moment — to inform one’s self, or else fall behind. It is basic knowledge that identities alone do not equate to emancipation for all and that identity in itself is not the end of the discussion. If one truly understands identity politics and intersectional feminism, this is common-sense. Only those who fight about the gaps in discussions that are equally present in any and all political theories are either extremely uninformed or willfully pit themselves against allies in a complex socio-political-economic issue instead of attacking the common enemy.

If a framework or theory has been co-opted by hegemonic powers, it does not mean that the framework is the problem. We problematize the co-optation that has precisely reduced it to “symbols” which, again, doesn’t mean that symbols are useless. They reduce it precisely because they know how powerful symbols are. Gramsci talks about hegemony and how public opinion is formed alluding a lot to symbols.

There is no simple, or blanket solution. It is in these differences that we commit ourselves to fight everything, everywhere, together.

Even within people who share similar material conditions, there are differences, and the only reality that’s truly shared among those people with different material conditions and political identities is oppression.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect DiEM25’s official policies or positions.

Identity, solidarity and DiEM25

If I were a transgender person and a bunch of Lefties dared lecture me that the exploitation of factory workers by capitalists is more important than my daily struggle tο function as a transgender person, I would tell them to get lost. No one has the right to tell those who are hurt, terrified, exploited or oppressed that their pain, fear or persecution is politically less important than some other type of repression.

Discrimination, we must not forget, divides and multiplies. It does so automatically because in so doing it gains evolutionary stability. The exploitation of a group is reinforced when its exploited members (eg. workers) get the feeling that they are not at the bottom of the pecking order but that there is a subset of their group (e.g. workers’ wives) that they can exploit. This pattern becomes even more entrenched when the subset of the exploited group is further bisected (e.g. between black and white workers’ wives). And so on.

Other patterns of discrimination can emerge from utterly arbitrary differences that, logic dictates, should be irrelevant. Left-handed schoolchildren, for example, have for centuries found themselves in lesser social roles, often grossly discriminated against — so much so that their lives are marked into old age. In laboratory experiments that I conducted in the 1990s, assigning a random colour to otherwise identical participants generated significant discrimination within minutes, with holders of one of the colours emerging spontaneously as the dominant group. (See here for a broad discussion and here for the relevant academic paper.)

In short, in every society hitherto, discrimination digs in by constantly inventing new divisions and opportunities for oppression. Even to imagine that there exists some objective metric by which to compare the different groups’ pain or deservedness, is ridiculous. Equally ridiculous is any attempt to compare your predicament to that of people of another group exposed to a different oppression. Finally, it is for each and every differently oppressed person to decide which type of oppression to rage against and how to fight for their future. The Left’s old argument, which I remember encountering as a teenager, that first we build socialism and then all other oppressions wither is not just stupid — it is oppressive.

Solidarity

Consider the extreme case of a black middle-class Harvard student. While it is meaningful, and statistically accurate, to say that it is easier these days for a black person to enter Harvard than for a poor person, it is both unhelpful and wrong to compare and contrast the two types of experience. Who are we to say that the black middle-class Harvard student’s terror at being stopped by police, and subjected to the ignominy reserved for blacks, is more or less crushing than the despair of a white poor person who did not get into Harvard but is attending Community College and works at some Amazon warehouse to make ends meet? Once we get bogged down in such comparisons, we lose the plot. Which plot? The plot which we should be following, namely building solidarity between people in the clasps of different types of pain, suffering and fear.

Power has a capacity to unite, to become abstract and homogenous in proportion to how exorbitant it is. This is why in Davos there is very little discrimination. Black and white, American and African, male and female corporate executives band together with remarkable equanimity. They speak as if with one voice. They never antagonise each other or fall out. If you ask them pressing questions about the role of structured derivatives, central banks or private equity, they will all give you the same, more or less, answer.

In sharp contrast, the powerless, the exploited and the suffering tend to disunity that renders them even less powerful. Each group, nursing its special pain, looks inwards and feels threatened both by the oligarchy and by other groups of disempowered people. It is in this manner that the poor and the disheartened are ‘persuaded’ to use their formal liberty (e.g. during elections) to keep wealth in power. Only solidarity across the ever-evolving archipelago of under-privilege can change this and challenge the oligarchy-without-frontiers.

DiEM25

“We come from every part of Europe and are united by different cultures, languages, accents, political party affiliations, ideologies, skin colours, gender identities, faiths and conceptions of the good society.”

When we got together at the Volksbühne Theatre to inaugurate DiEM25 on 9 February 2016, we had indeed arrived from all over Europe, in difference but also in solidarity.

We celebrated our gathering by committing to “treating non-Europeans as ends-in-themselves”, to remaining “…alive to ideas, people and inspiration from all over the world, recognising fences and borders as signs of weakness spreading insecurity in the name of security”; and to struggling together for a “…Liberated Europe where privilege, prejudice, deprivation and the threat of violence wither, allowing Europeans to be born into fewer stereotypical roles, to enjoy even chances to develop their potential, and to be free to choose more of their partners in life, work and society.”

That was DiEM25 on the day it was born five years ago. This is DiEM25 today too. At a time when divisions (also known as culture wars) are wreaking havoc amongst progressive people who should know better, we have an opportunity to use our differences as building blocks of the one thing that can face down the dividing-and-multiplying oppressions spreading like rampant bushfires in our post-Covid-19 world: Solidarity!

To build solidarity, DiEM25 is constantly working for a common plan against every single oppression. Is such a common plan possible given the variety of oppressions? Of course it is. Green shared prosperity is technically possible and an excellent foundation of turning the tide of multiple oppressions to reveal a terrain on which different people can lead equally flourishing lives. However, it is one thing to say it is feasible and quite another to make it happen. For this we need common campaigns.

And here is where progressives, and the Left in particular, are failing so badly today: On the one hand, we have the time-honoured divisions due to power-struggles over bureaucratic nation-state-based parties. And on the other hand, we have the tendency of different groups to separate their struggle from those of other groups. Also known as identity politics, this is the opposite of solidarity — a godsend to the Davos men and women whose power is thus guaranteed.

That’s why DiEM25 is so important: Not only is it the only transnational European political movement (with a paneuropean manifesto, one set of detailed policies for the whole of Europe, a unique Feminism, Diversity and Disabilities Taskforce etc.), but it is also the foundation of the Progressive International which, in the last eight months, has shown what international solidarity means in practice.

Through our Make Amazon Pay campaign, the Debt Justice Collective, our electoral observatories in Latin America, the farmers’ strike in India etc. we have demonstrated the one thing that matters: To liberate everyone, we must act globally against every single type of oppression, without privileging one type of suffering over another, by turning our sovereign and multiple identities into one tsunami of humanist solidarity.

Carpe DiEM25!

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect DiEM25’s official policies or positions.

Read more opinions about this topic.

The self and other in a globalised world

A new year invites reflection on how we want things to be different. It’s hard to believe that as recently as twelve months ago, the impending coronavirus — and the vast socioeconomic inequity it now exposes in stark relief — had yet to reach public awareness. As we survey the magnitude of political, economic, and social disparity on which corporate interests quite literally continue to capitalise, how do we situate ourselves psychologically for 2021?

A lot rides on answers to this question because we have long known that the personal is political. Despite ongoing oligarchical attempts to deflect recognition of this, individual and collective well-being are intertwined. So what kind of person do we aspire to be in the kind of society in which we live?

Subjectivity under neoliberalism

Contemporary neoliberalism presents a distorted reading of autonomy in which individual interest is celebrated at the expense of the social input and effort which makes it possible. But since its emergence in the historical context of the eighteenth-century European Enlightenment, liberal ideology per se has failed to recognise the extent to which ‘the self is a product of social processes, not their origin’.

Issues of identity are now prominent in public debate. But personal identity is constructed relationally, by social and group processes of which the liberal tradition has long taken insufficient account. In illegitimately counterposing ‘individual’ and ‘society’ — one of many dichotomies on which the liberal tradition rests — individuals are detached from the social contexts which shape them.

In contrast to classical and current neoliberal premises, we are interdependent rather than autonomous.

This applies to mental health no less than to politics and economics. It also has implications for what it means to be well in globalised societies.

Parallels and also pathologies between internal and external regulatory systems are clear. The `dysfunction of key regulatory systems — both individual and social — were observed nearly two decades ago: “The signs that something is amiss in our inner mechanisms of control and restraint are everywhere… Not only physicians and traumatologists but sociologists are pointing out parallels between growing rates of individual and societal trauma.”

Both are escalating in the current period. The impacts of the coronavirus, raging fires in many parts of the world, and environmental devastation are obvious illustrations. Their wide-ranging impacts are compounded by the erosion of the public sector and services and by pervasive corruption (for example regarding the recent explosion in Lebanon) and the calculated policies of austerity.

The parallel between external and internal system failure continues to be marked. The recent text Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism charts in disturbing detail the relationship between socioeconomic devastation and psychological and physical destruction such as declining marriages, and increased rates of suicide and addiction. Yet our culture remains replete with compartmentalisations which are ruthlessly and shamelessly exploited by neoliberal oligarchical interests.

It is simply incorrect to counterpose autonomy and dependence. The mantra of individualism notwithstanding, life is inherently relational.

Mental health is routinely described in individualist terms. But how is psychological well-being possible in societies which are unhealthy?

A Turkish psychiatrist and clinical psychologist have described how integrated psychological functioning is disrupted by societal (not just ‘individual’) processes under the oppressive conditions of late capitalism. This can occur both by over-stimulation (eg. exposure to 24/7 media cycles) and under-stimulation (via the absence of meaningful work, underemployment or no paid work at all).

Emotional well-being is not influenced solely by temperament or ‘the family’ in isolation. It is shaped by wider societal structures in which increasing numbers of people across the globe struggle not only for basic economic subsistence, but also for minimal conditions conducive to coherent psychological functioning.

Mental health has become corporatised

The misconception that ‘private’ and ‘public’ can be counterposed feeds the illusion that our ‘internal’ and ‘external’ worlds are discrete. While we know that this is not the case (e.g. the subliminal power of advertising) we may feel differently. In his aptly named text The Political Psyche, Andrew Samuels notes that “subjectivity and intersubjectivity have political roots; they are not as ‘internal’ as they seem.” The reality is that in neoliberal societies and economies, few domains are immune to the influence of market forces.

The values and priorities of the ‘psy’ professions, no less than other industries, are underpinned by the tenets of the liberal culture in which they operate. Psychiatrist and cultural critic David Healy is explicit that as far as the dynamics of late capitalism are concerned; the field of psychiatry is no `special case’. His claim is that the advent of ‘a new corporate psychiatry’, paralleling the rise of corporate capitalism, raises issues we have barely begun to address:

“Galbraith has argued we no longer have free markets; corporations work out what they have to sell and then prepare the market so that we will want those products… It works for cars, oil, and everything else. Why would it not work for psychiatry?”

Indeed, the strength of corporate culture – and the capacity to market as much as treat `disorder’ – displaces the authority of medical discourse itself. This is because the marketing of science shapes cultural beliefs not only of how we regard experiences of depression, but how we regard health and normality.

Healy speaks of a shift which is as much commercial and cultural as medical and scientific. Comments he made over a decade ago have new salience in light of how far the phenomenon he describes has taken root:

“A huge gap has opened up between what is scientifically demonstrable and what people believe, pointing to a cultural phenomenon that lies well beyond the `medicalisation’ so worrying to sociologists and bioethicists…There is something here that reaches down to the level of the myths we make to live by. Our ideas of what it means to be human are at stake.”

Pharmageddon conveys both the power and public health risks of an industry which has the capacity to market (and not just treat) what ‘disorder’ is considered to be. The capacity of corporate psychiatry to shape the deepest reaches of our subjectivity is disturbing.

Diagnosing the polity

Oppression exists within, as well as outside, ostensibly democratic countries. Yet this remains difficult for many to acknowledge, because oppression is defined by liberal ideology as external to western societies. Like the capitalism it enables, and as Yanis Varoufakis points out, neoliberalism facilitates both spectacular technological innovations and new forms of depravity. But its capacity to corporatise and commodify mental health — to the point of shaping ‘what it means to be human’ — is an insidious form of reach which remains less recognised because it is less obvious.

Consistent with the claim that oppression is enacted in ‘the everyday practices of a well-intentioned liberal society’, the corporatisation of mental health has occurred in part because of attempts to regulate the environment in which medication became available. Yet changes in the patenting laws of the 1960s accelerated the prevalence of antidepressants in western societies, at the same time as making many new drugs inaccessible to the most vulnerable populations of the world. The current monopoly of COVID vaccines by so-called `developed’ countries is a striking continuation of this inequity.

The patenting laws were also a further step in the privatisation of research and knowledge which has been compared to the loss of land held by English villages and communities prior to the sixteenth century enclosure laws. In an ironic inversion, social problems are privatised in neoliberal economies and individuals are held to be responsible for their distress. Depression, emotional blunting and desensitisation increase as attempts to meet the `norms’ of mental health become increasingly difficult in increasingly inequitable societies

Depression has long been regarded as an epidemic within western societies and is now concurrent with a literal pandemic. The manifest failure of the governments and neoliberal economies of the UK, United States, and many European countries to safeguard public health in the age of the coronavirus is apparent to all. The mental health impacts of this mismanagement are only beginning to reverberate.

Developing countries can indeed teach rich countries about how to respond to a pandemic. Their strategies of `doing more with less’ highlights the disparity in ethics, as well as resources, between what it is no longer appropriate to describe as the `developed’ vis a vis `developing’ worlds. What are the implications in terms of the kind of person we might aspire to become for those of us who have the luxury to ponder the question? How we begin to answer this question depends on how we define `person’, and the qualities and attributes which distinguish personhood.

Becoming a person

While widely taken for granted, the qualities that define personhood are debated in various disciplines. In considering the role of consciousness as sufficient criteria, neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux poses the provocative questions: ‘Does a person have to be human? Are all humans persons?’. Contrary to popular belief, the terms ‘person’, ‘individual’ and ‘human’ are not synonymous.

One of the several reasons for this becomes clearer when we consider the sad but incontestable fact that being human is not at all inconsistent with behaving in ways which are widely regarded as inhumane. The continuing legacy of liberal counterposing of ‘individual’ and ‘society’ is pernicious in deflecting attention from the crucial importance of the social contexts in which we exist and which profoundly shape who we are and can become.

The kind of person we are — and how kind we are in the sense of generosity, cooperation and care for others – cannot be considered in isolation from the characteristics which are promoted and rewarded (or conversely discouraged and penalised) in the societies we inhabit. Yet in privileging market-place ‘individualism’, consciousness, and rationality (which is frequently deployed to rationalize the results of unbridled competitiveness) there is little in the ideology of liberalism that speaks to ethical capacity or need.

Self-interest is self-evident. But it is far from all that motivates human beings. It is also a tenet of liberal and neoliberal ideology which needs to be reappraised. This is because there are major senses in which concern for and about the needs of others is conducive to our own well-being. The limits of perceived self-interest detached from ethical concern are apparent in the case of Arturo Lascanas. A self-confessed hitman and subsequent accuser of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, Lascanas was described as ‘dishevelled by guilt’ on implementing orders that violated a moral code he hadn’t paused to consider he possessed.

Indifference to the well-being of others entails personal costs as well as benefits for persons who are not sociopathic. And the absence of empathy precludes the status of personhood in the full sense of the term. It is in our own interests to work towards the type of societies in which the well-being of others is a consistent high priority. If human beings act in ways which are unconscionable — if we lack or lose access to our consciences — what kind of people do we become?

Photo Source: Photo by Alex Green from Pexels.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect DiEM25’s official policies or positions.

Stand as a candidate for one of our National Collectives

Apply now!

Our members passed new measures for the election of our National Collectives, meaning that we have been in the process of re-electing all of our national coordination teams.

The countries whose elections are open for candidates are:

If you are interested in standing for election for our team in one of those countries, please click on the respective link above, read the criteria carefully, and if you meet them please submit your application via the link!

The deadline for these elections is 24 January.

Carpe DiEM,

DiEM25 Coordinating Collective

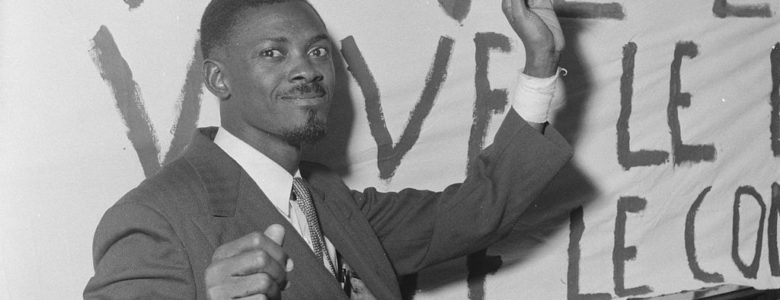

The Internationalist: Long Live Lumumba!

The Progressive International (PI) commemorates Patrice Lumumba — the first Prime Minister of the independent Democratic Republic of the Congo

On the 60th anniversary of the assassination of Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961), PI Council member Vijay Prashad lead a wide-ranging discussion about the legacy of the Congolese pan-Africanist — and the impact of his assassination on the Democratic Republic of Congo, Africa, and struggles for national liberation everywhere. It is part of The International, a new weekly program by the PI that brings you news from the front of our struggles around the world, connecting across territories and oceans, nations and generations.

“You are going to kill us, aren’t you?”

Those were the last words reported of Patrice Lumumba.

Patrice Lumumba and his comrades Joseph Okuto and Maurice Mpolo were brutally killed by the Belgian intelligence services. The impact of this event continues to be felt across the world. In Vijay Prashad’s introduction, he states that the Progressive International is calling for ‘Lumumba Day’ to be implemented on 17 January:

“Today we also want to celebrate his legacy and remember the impact his death has had on the African continent and the whole world in general. We see that though it has happened 6 decades ago it is still as relevant as ever.”

“On Lumumba day, we are calling for all debts — external debt — to be cancelled, for the people of Africa to be treated with dignity, for recognition of the theft of resources for generations from the continent.”

Watch the event now!

Highlights

Kambale Musavuli (Centre for Research on the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

“The Congolese today know why [Lumumba] was killed. He was killed because he wanted the resources of the Congo to benefit the Congolese people. That idea was part of a process — a process of Africans wanting to determine their affairs.”

“Even though they put his body in acid and kept a tooth as a trophy in Belgium, Patrice Lumumba lives today through our culture, our music, our history. Even when they lie about the story of Lumumba — who that young man was and how he wanted to liberate the Congo — young communists today are standing up. As we are doing this event at the moment, today, right at this minute, thousands of Congolese are in front of the Lumumba statue, celebrating, commemorating, Patrice Lumumba, knowing that the fight that he asked us to do in the last letter to his wife is not finished. He said that he rest assured that the generations of the future, the Congolese of today, will not stop until there are no more neocolonial agents are in the Congo. And that is the fight that the Congolese youth is taking until today and we know for sure that we will be victorious in this struggle and definitely calling on all people around the world to join the Congolese and Lumumba call so that his ideas, his vision to liberate the Congo, comes in our lifetime.”

Marie-Claire Faray (Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom)

“Patrice Lumumba was a tree that was cut. However, what those who cut that tree didn’t know is that Patrice Lumumba bore seeds and those seeds will always grow more trees.”

“In Lumumba’s writing and speech there is a clear passion and commitment to decolonise the Congo as well as decolonise the minds of his fellow citizens — women and men alike. In his essay, ‘Le Congo, terre d’avenir, est-il menacé?’ Lumumba clearly mentions the objectification of women and the restoration of the status of Congolese women in the society.”

Nanjala Nyabola (Progressive International, Kenya)

“Some European authors avoid reporting the fact that it was the Belgian government who oversaw the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. (…) How can we build a shared understanding of what the objectives of decolonisation are if we don’t even agree on what colonisation was. If African generations are growing up and trying to reclaim this sense of pan-Africanism and reclaiming this sense of self from the violence and toxic waste that was colonisation but European generations are being told that it wasn’t that bad, it was actually a process of civilisation and all of that stuff.”

“The denial about what [colonialism] actually did and actually continues to do is part of the harm that many societies in Africa are struggling to get past as they try to think and imagine what a positive future would look like.”

“What does accountability for this violence look like? (…) What do we actually want healing and reckoning to look like?”

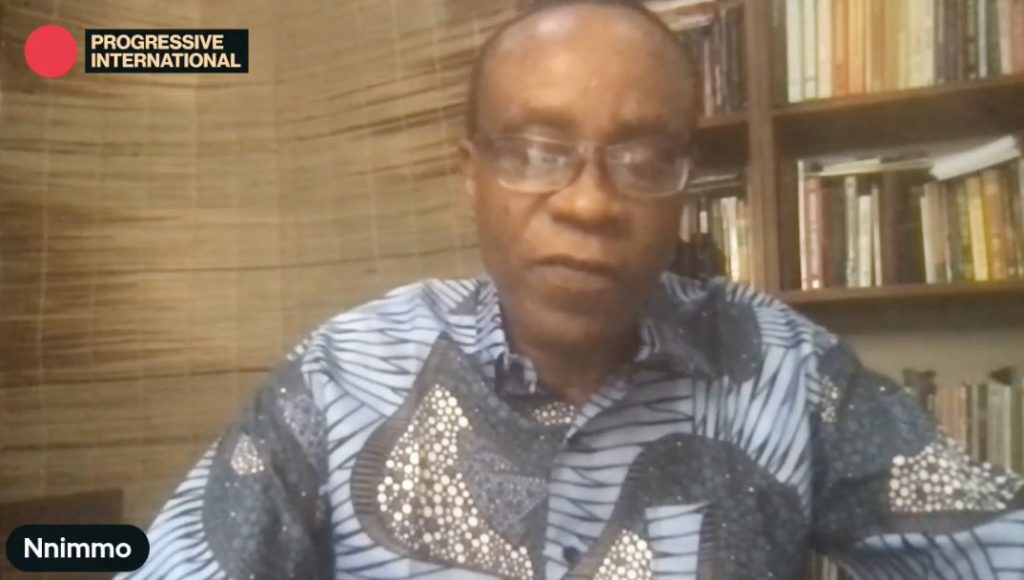

Nnimmo Bassey (Progressive International, Nigeria)

“It’s really time to cancel those odious debts. It’s time also to speak about the ecological debt. Who will pay for the ecological destruction of Africa? Who will pay for all the mindless, irresponsible destruction that has gone on in the continent for hundreds and hundreds of years. This debt is something that should not be ignored continuously; it’s time to admit that with such a debt we should all demand that it be paid. Africa is actually a net creditor, not a debtor continent at all.”

“The myth that Africans cannot govern themselves has made it that whenever there was a shining light, there was a chance that a leadership would bring true progress in the continent defined by the continent and in part defined by the citizens of the continent, that was not acceptable. To sustain the myth that Africans cannot govern themselves, every light had to be forcefully removed from office or assassinated.”

“The material things we have must not be the material things that kill us.”

Vashna Jagarnath (Pan-Africa Today)

“These sorts of spirits almost, the resurrection of our revolutionary ancestors, need to become active lessons for us in our fight against imperialism. And I think one very vital that we should also take forward from this — and it is something that since the 1980s has been in the background of this discourse when you think about liberationary discourse — is the role of socialism and communism within these movements. And we cannot underplay those because they are vital in order to undo the sort of ways in which the imperial powers divided this continent and the ways in which they extract and exploit this continent, both in terms of human resources, intellectual resources, and atual material resources. ”

“For Fanon, the assassination of Lumumba along with the rise of this compromised nationalist elite set the tone for what was going to happen on the African continent for the next 40 years.”

Kwesi Pratt (Socialist Forum of Ghana)

“Congo has enormous resources. It alone has the capacity to provide for all of Africa’s electricity needs. Why are many of our people living in darkness today across the African continent? All of the West depends on the Congo for resources to advance their economies.”

“Look at the kinds of leaders we have on the continent of Africa today. Neo-colonial leaders who have lost any sense of dignity. Africa will rise again. And it will rise under the banner of scientific socialism.”

“We continue to live in the quagmire of poverty. Why is that so? It is because we have been unable to delink from the colonial metropolis. It is because everything that happens on the continent needs to enlarge the bank accounts of corporations from the colonial metropolis.”

“That we continue today to work for the building of socialist societies is a defeat for those forces. And we shall continue to defeat them day after day, week after week, until we build that society — in which all human beings have value, in which no child goes to bed hungry…”

It is time for progressives of the world to unite. Show your support. The Progressive International on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Stop the war in Yemen

DiEM25 recognises the immense humanitarian crisis that has engulfed Yemen. We have an ethical duty towards the Yemeni people to support coalitions that seek to cease this senseless war. A solidarity campaign devoted to ending the humanitarian crisis destroying the region will only be successful if the international community shows unwavering and massive support for the “Stop the War in Yemen Campaign”.

Our responsibility includes denouncing the complicity of Western governments in prolonging the deadly 6 year-long humanitarian crises in Yemen. We must insist they use all means to stop the war and help advance peace in Yemen. We demand that our governments cease violating the Arms Trade Treaty and halt all arms sales to belligerents involved in the conflict. All legal avenues must be pursued to investigate the violations of international humanitarian law and arms control regimes by all parties involved and benefiting from this conflict.

We demand that the incoming Biden administration reverse the designation of Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organisation by the outgoing Trump administration. This classification has the real-world effect of severely disrupting humanitarian aid for the 20 million Yemenis that live under Houthi control – with aid organisations having to choose between violating U.S. law or ending their humanitarian and peacebuilding actions in Yemen. This designation creates conditions tantamount to collective punishment and must be revoked.

We will hold our respective governments along with their partnerships with private institutions accountable for their role in fuelling hostilities through rhetoric and divisive political and economic tactics and for their role in exploiting insecurity in the entire region.

Photo Source: Global Risk Insights.