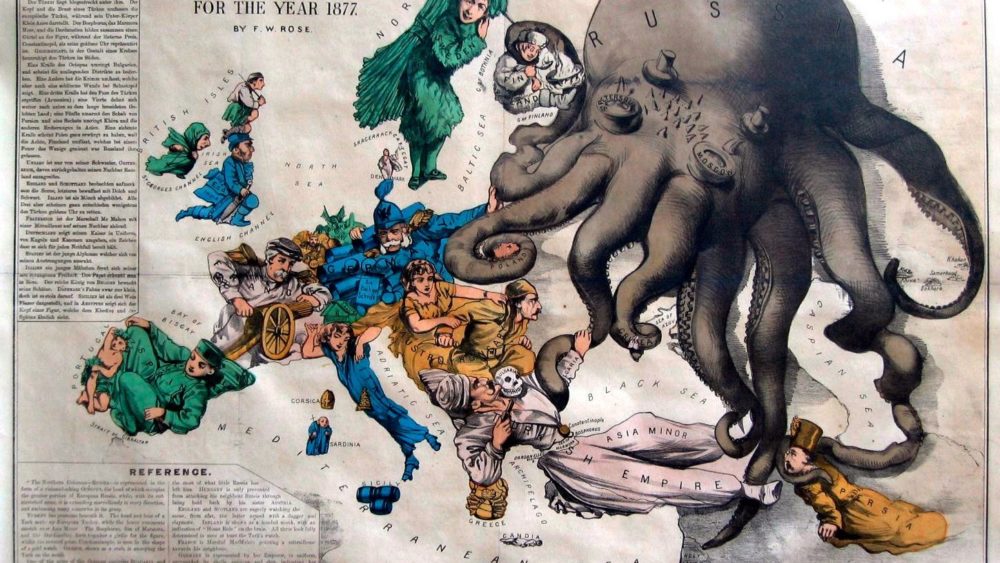

Eurobonds and solidarity have been the watchwords for the last three weeks. Mediterranian countries have been especially loud on the need for the Eurozone to unite to fight the COVID-19 crisis efficiently. But the eurozone is more divided than ever, with a few countries, headed by the Netherlands and Germany, rejecting debt mutualisation (e.g., Eurobonds). Not only is the economy at stake; so is the political stability of the EU — with national pride sentiments gaining momentum amidst this internal confrontation. But is this a fight between countries, or a struggle of the classes, “corporatism style”?. The answer is no further than a quick, quarantine-proof trip to 19th century Europe.

Revanchism, a nationalist sentiment for revenge spread in public opinion, has been a major political tool in the old continent.

In the 1800s, the solution that was used to redeem loss of territory or influence was the inhumane ‘Scramble for Africa’. The French, humiliated by the post-revolutionary and Franco-Prussian wars, were ‘offered’ Algeria and Tunisia in order to appease its political leaders. The Italians were not happy with the Tunisian deal, so the English were always favorable to their conquest wars in Abyssinia. Germany’s colonization of Namibia and Tanzania was allowed in exchange for Bismarck’s sympathy with the British in Egypt. When there were no more pieces of Africa to negotiate, the Great War broke out.

This is a rather simplistic summary, but enough to make my point that, between 1871 and 1914 (43 years) Europe lived a long period of peace, strong diplomatic activity, and steady economic growth (deduced from GDP), similar to that we have experienced since the end of WWII. Looking at the history of the GDP per capita in England, we see that both periods (1871-1914 and 1945-2009) ended in an abrupt drop. We can conclude that 19th century Europe superficially resembled the days in which we were all born, both economically and politically.

In politics, there were election-winning technocrats that manipulated public opinion with the support of trade and industrial companies interested in acquiring new markets and goods in Africa. At the same time, colonial expansion was also made possible thanks to bankers ready to make a profit out of public debt growth. It happened the same way in Germany, Italy, France, Britain, or Portugal.

Today, as in the late 19th century, politicians are more similar to workers in a nail factory than to philosophers, to use Smith’s terms. At times, it seems like the trade of politicians consists in selling the power they gather from voters to the highest bidder. They make concessions to voters in order to get their support, but then use it to please big corporations with favorable deals such as market monopolies or reduced labor wages. Most of the time, politicians offer the voters a compromise or simply influence public opinion through the media.

When the German finance minister forces economically illogical agreements at the Eurogroup, or the French side acquiesces against its own interest, it is because their government needs to gather support from the wealthiest 1% to buy the vote of the virtually property-less 99% of the population. On the one hand, Germany’s Merkel acceptance of the Eurobonds might put an end to the fragile CDU coalition government, and likely defeat in the next elections, with the far-right waiting to take control. On the other hand, the reckless use of the European Stability Mechanism bailout fund to create a “rich EU” protectorate on Southern Europe (as in Greece or Portugal in 2011) will shred cohesion in the EU.

The point is, revanchism is completely useless. Dutch, Germans, Austrian, and Finnish are not heartless monsters because their governments reject to take an economically and morally just and efficient option (e.g., Eurobonds). Nor should the Mediterranian be regarded as defenders of the faith because of their chivalrous outcries for solidarity and justice.

The current impasse and incapacity to respond to the COVID-19 crisis and to prepare the reconstruction of European economy is not due to philosophic divergences among politicians, but rather to the lack of transparency and accountability in European politics.

The ‘economy’ — the wealthy speculators and monopolists — always gets the upper hand in Europe, mainly through their influence in non-elected informal meetings such as the Eurogroup (as has been reported by Euroleaks) and due to the European Commission’s opaque democratic processes. The Commission is the executive branch of the EU which holds, among other important roles, that of proposing legislation.

This “European government” indirectly depends on direct suffrage, but the overcomplicated election process leaves its composition to close-door negotiations between the heads of national governments (European Council). Take as an example the current president, Ursula von der Leyen, who was approved by the European Parliament without ever being a candidate. Moreover, despite the voluntary registration of lobbyists in the European Commission, the European Council lacks transparency at this level.

While this lack of transparency and accountability leaves the pledges of the European people unanswered, tensions between member-states are being used by far-right movements to project their power.

Nationalism thrives by giving simple solutions to complex problems affecting the front-line communities, as clearly laid on a recent essay about fascism. The masses, all across Europe, are being put at the risk of poverty due to the promiscuity between the political and the market economy spheres that has served as the basis of Western societies for many years.

In the EU, the common market and the common currency coexist with country-specific debt, with no European minimum-wage, or common fiscal policy. This reduces the power of national parliaments to tax and rule, and leaves a European legitimacy vacuum for big corporations to exploit, with serious implications for the masses. The Portuguese stock exchange provides a caricatural example of this vacuum, with the 20 most valuable companies featuring holdings with a seat in the tax-friendly Netherlands. This results from the lack of a commun fiscal policy in the EU, and the inefficiency of the most essential lobbying mechanism, the vote (as explained above).

In sum, the division in Europe is not only between the Italian and Dutch, or Greeks and Germans, but between the unchecked powers of big capital and the oppressed and voiceless people of member-states. The EU will not be saved through discussions within the Eurogroup or even at the level of the European Council. These are temporary, often fragile, and frequently condemned to failure (as in 1914). National pride and jingoism do not address the structural problems of the system, and only creates the perfect environment for senseless divisions to thrive.

The only way to put an end to the European crisis that has lasted since 2008 is to ensure increased transparency in the Union.

This will allow for a redistribution of wealth and rebalancing of European society under a truly democratic system. In order to survive the COVID-19 crisis and launch the basis for a true European Federation, the common market is not enough.

In the EU, capital moves freely and the labor market has no borders. Debt must therefore be common to all member-states. If the ECB issues Eurobonds immediately (Step 1 of DiEM25 anti-depression plan), all countries will be given equal tools to counter the consequences of the coming economic recession. If instead of having member-states bailing out their banks, the commission also injects money in peoples’ pockets (Step 2), the real economy will be protected and poverty will not spread. At last, Europe needs to prepare for the future (Step 3), not with a Marshall plan based on fossil fuels and speculation, but with an innovative green investment program.

While the subject of debt mutualisation still divides national governments, the idea has gained momentum with the European Parliament’s approval of a joint motion featuring a formal advice for the creation of European bonds. Although this is a non-binding proposal that implies limited shared risks, it highlights the important role of an elected institution in lobbying for progressive and ‘federalizing’ measures.

Either we fully embrace the European project, or our depleted and exhausted governments will embrace nationalism. History contains many testimonials of the disastrous consequences of nationalism and European fragmentation.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here