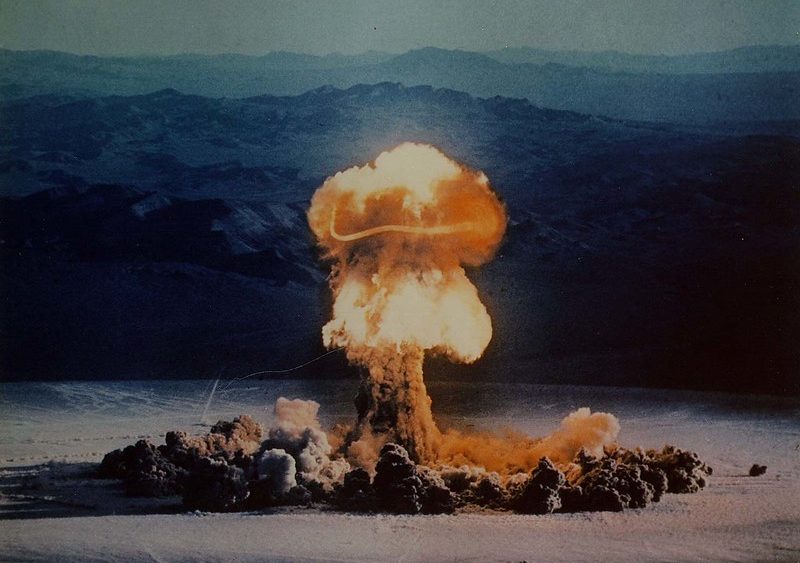

As stated in our article on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), there are several reasons to celebrate its recent enforcement on 22 January. Firstly, it constitutes a progression in international law. Secondly, it’s a hopeful symbol for nuclear disarmament struggles around the world. And thirdly, it provides third-world-countries with a positive occasion to oppose Northern dominance. The treaty’s real world effects on the reduction and elimination of nuclear weapons remain questionable, and in fact, are likely to be low, unless certain conditions are met.

It may be regarded as too early to give an assessment of the treaty’s success, as it is still in its infancy — but one glaring fact might nonetheless already allow one to take a bold stance on the matter. Namely, that neither any of the 9 nuclear weapons states, nor NATO are part of the agreement — thereby seriously undermining its stated goals from the outset. It is evident that any treaty that aims at prohibiting nuclear weapons must include the nations that hold nuclear weapons and those who support them in doing so. Without them any vision of a nuclear-free world must remain empty.

In a public statement issued with regard to the 2017 UN-conference, which initiated the treaty, NATO summarized the North’s stance on the whole matter quite aptly by simply stating that “as long as nuclear weapons exist, NATO will remain a nuclear alliance.” In other words expressing that NATO (and therewith the nuclear weapons states within it) will not move an inch from its own volition to overcome the threat.

The other nuclear powers (outside of NATO): Russia, China, Pakistan, India, Israel and North Korea, are likely to follow suit. That is: remain unwilling to enter commitments, which would have them reduce and terminate their nuclear arsenals, as long as doing so would result in them gaining a disadvantage over their fellow nuclear weapons states.

Where must the initiative to vanquish the danger of nuclear weapons come from, if not the main military alliance in the world or the states that hold these weapons?

It certainly won’t come from the military industries which directly profit from the proliferation of the threat by their manufacturing and distributing of the weaponry. According to a report by Dutch peace organisation PAX, governments around the world are currently contracting 116 billion US dollars to private sector industries in the manufacture, development and maintenance of nuclear weapons.

The corporate sector, in turn, seem to use nuclear weapons as a pressure device, by which countries inclined to economic independence can be coerced into submission. The state disguises threats the same way that a robber uses a gun to get a cashier to empty the register for him; without actually having to use the weapon, but simply by benefiting from its threatening presence (a point Daniel Ellsberg has repeatedly stressed). Thereby, by “cast[ing] the shadow of power across the bargaining table” (former US Secretary of State, George Schultz) — or the shop counter, we might say, to remain in our picture — getting the pressured country to open up its markets and resources to foreign capital penetration.

This is a strategy which we can find expressed in the US Strategic Command’s “Essentials of Post-Cold War Deterrence” — a 1995 study by the defense department agency on “the role of nuclear weapons in the post-Cold War era.” In it, STRATCOM advises US planners not to adopt such “declaratory policies” as “no first use” (of nuclear weapons) — but instead to maintain its right to a first strike-capability, even against non-nuclear states. It goes on pointing out that “nuclear weapons always cast a shadow over any crisis or conflict in which the US is engaged” and that it is therefore prudent to maintain them. It further adds that:

“It hurts to portray ourselves as too fully rational and cool-headed. The fact that some elements may appear potentially ‘out of control’ can be beneficial to creating and reinforcing fears and doubts within the minds of an adversary’s decision makers. […] That the US may become irrational and vindictive if its vital interests are attacked should be a part of the national persona we project to all adversaries.”

We can see this “irrational and vindictive […] national persona”, “creating and reinforcing fears and doubts within the minds of an adversary’s decision makers”, at play each time a US president announces to a designated enemy state that “all options are on the table” — including nuclear weapons. Thereby, by “cast[ing] a shadow” over the conflict, incidentally also violating international law. Namely, the UN charter, which happens to ban not only the use but also the threat of use of force, unless explicitly authorised.

Given the interests that motivate these sectors (state and private), to maintain and expand the nuclear capability of their respective countries, we can dismiss the possibility that a move toward abolishing it will come from them.

Which faction will be open for an initiative toward ending war remains in society, if it is not the state or private sector?

There is one agent in human affairs which has historically shown itself to be the main driving force behind social change — as moral progress in general: the general population. Be it factory workers in 19th century Britain fighting for the 8-hour working day and a decent wage, or German workers pressuring Reich Chancellor Bismarck into establishing the first ever national social security system in the world in 1883 (since adopted by most advanced industrial countries around the globe). Or the so called Freedom Riders: groups of white and black civil rights activists in the United States, riding buses through the south in the early 1960s, using “whites-only“ lunch-counters and restrooms at bus terminals in an attempt to overcome segregation. Or the feminist struggles, taking their origins — at least in the West — in the early parts of the last century, expanding into full-scale social movements in the 1970s and since shaping life like perhaps no other social force. Or — to draw from very recent history — the many, predominantly, young people involved in ecological movements around the world today, such as Fridays for Future or Extinction Rebellion, calling for attention to and action on the threat of ecological disaster.

All these examples of social movements show us what progress has been made and indicate what could lie in the future, if concerned people unite on such issues and demand those advances which so far they have been denied.

So too on the nuclear front. Here, people from North and South should conjoin their efforts to collectively exercise pressure on those who are currently endangering species survival with their pursuit of profit above all else (even human existence); Corporations, to restate, by seeking the profits and states by abetting them in it. Profits, again, which are made either directly through the manufacture and maintenance of nuclear weapons or indirectly through foreign capital penetration under the barrel of the nuclear gun.

These vile motives mustn’t be the only ones considered, when the question is asked: what of nuclear weapons? They must be contested and countered by people everywhere with an argument against institutionalised greed and for the preservation of human life. One organisation already doing that is ICAN: The ‘International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons’.

The realisation of the TPNW — its actual impact notwithstanding — has been through the tireless campaigning of nearly 600 non-governmental organisations in 100 countries. These organisations came together under the ICAN which took inspiration from the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL). That campaign led towards the eventual entry into force of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention.

ICAN, ICBL and other civil society organisations active on elimination of weapons reflect two important and positive tendencies in the shared struggle. Firstly, these coalitions represent renewed cooperation across North-South divides, compounding social pressure on actors engaged in the nuclear weapons industry. Secondly, the vast international network provides an additional space for people-to-people dialogue and strengthening of solidarity networks dealing with the existential threats facing humanity. Further campaigning — coupled with the new international norms set by the TPNW — will broaden and deepen public discourse and awareness on this issue.

To realise the ideals of the TPNW, we require nuclear weapon states to sign onto the treaty — a feat which, while elusive, can only be achieved through the pressure of sustained mass activism.

Activists need to focus on these arguments to pressure states into formally participating in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)

Europe should abide by its own legal commitments. That is, in this case, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Which under Article VI states that its members are to pursue “good faith” efforts to reduce and abolish nuclear weapons. A significant step toward reaching that goal would be made if European states signed onto the TPNW.

In addition, non-nuclear weapon states that hold nuclear weapons within their borders (four in Europe) face two additional threats; that of coming under pre-emptive attack and of accidental detonation. Although the probabilities of such occurrences are low, the resulting impacts are too devastating to even be considered as acceptable possibilities.

Furthermore, non-nuclear weapon states place enormous faith in the belief that they will be protected in the case of a nuclear attack by the nuclear weapons capability of their allies — the so-called nuclear umbrella. This is supposed to act as a deterrent against a potential first strike. This reliance on the allies’ nuclear arsenal for protection however, rests on very thin ice, since it is based on “political commitments or official statements” only. In other words, no explicit obligation — emanating from treaty texts — exists which will require the use of nuclear weapons in response to a nuclear attack. This is the case for both NATO and the security arrangements that Australia, Japan and South Korea have concluded with the United States. Dr. Jeffrey Lewis, in the case of Japan and South Korea, encapsulates this mirage as such:

“The so-called “nuclear umbrella” exists only because the United States is pledged [emphasis added] to defend Japan and South Korea and happens to possess nuclear weapons. The rest is left to the imagination.”

Since it is “left to the imagination” we might as well disband this argument for our allies’ nuclear weapons — and our supposed protection under them.

Our collective responsibility on the issue of the nuclear threat and its impact on the future of humanity necessitates action from all of us. To restate the stark choice that Albert Einstein and Bertrand Russell put before the world in their famous 1955 manifesto: “Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war?”

This article was authored by Amir Kiyaei and Tom Stopford who are members of the Peace and International Policy DSC.

Photo Source: International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear War on Flickr.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here