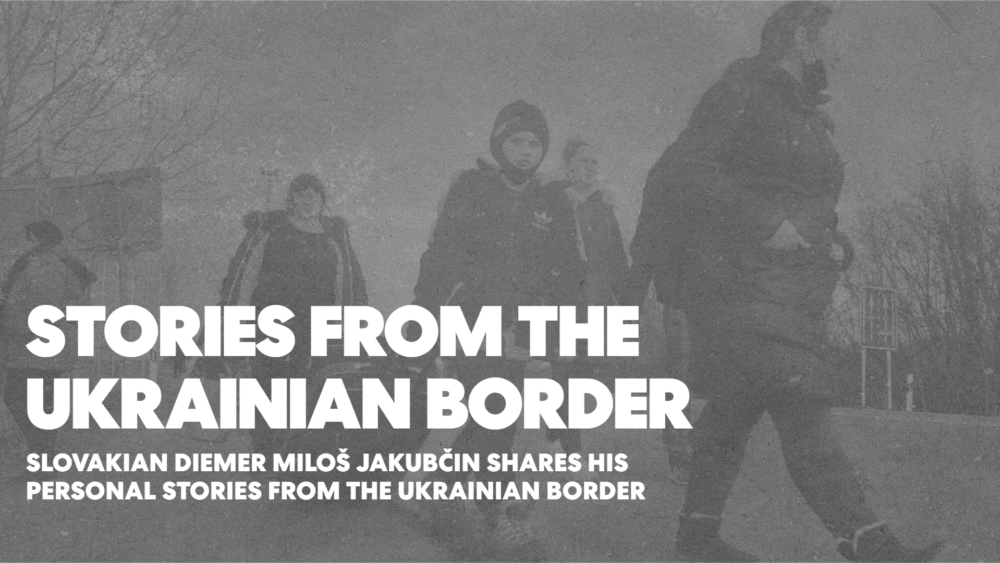

Slovakian volunteer and DiEM25 member Miloš Jakubčin shares his personal stories from the Ukrainian border.

Escaping a war zone is a journey that no person should have to make in their lifetime, yet that is the reality facing countless Ukrainians amid this ongoing conflict.

Miloš Jakubčin, a volunteer in Slovakia and a DiEM25 member, recounts some of the personal stories he has been a first-hand witness to in recent weeks.

From the beginning of the day, an uphill struggle ensues to assist with the various families looking to find refuge.

Four of us leave from Košice, Slovakia, at 04:00 in the morning, I take two Ukrainian friends, and the shift in Ubli starts at 06:00. We come to a hall full of beds with sleeping children. There is silence, peace everywhere. We look around, we get improvised training lasting a few minutes.

At around 07:00, the first buses arrive from the border. I hand my luggage to five women heading to Prague and, for the first time in years, I dust off my broken Russian. The day is slowly starting.

The lady gives me 300 Czech crowns and asks me to top up her phone credit. The mother of a little girl with abdominal pain is looking for a doctor. In a tent, tonnes of family suitcases are already waiting to be transferred. Potential transport must be called for the lady who is shaking on what is a chilly morning, with a small baby and a large dog.

A lady with bloodshot eyes emerges from another van, followed by two small children. The fire chief whispers to me: “This lady needs a psychologist.” We take the lady with the children away and look for a psychologist who hasn’t yet arrived. A chaplain has offered himself, but he needs an interpreter to talk. An interpreter is being sought.

A young boy turned 11 years old the day before. His view is already more mature than most people in their thirties in Slovakia. A teddy bear from a commercial airline as a gift is just a small consolation. At the very least, they managed to get transit to Krakow.

DiEM25 members protest outside the Russian embassy in Bratislava

Even from one volunteer’s first-hand experience, it becomes evident that those seeking refugee come from all walks of life.

A distraught old lady sobs in her fur coat. With a daughter, niece and four children, they need to be accommodated for a few hours, and so we begin to look for beds.

A father and seven Roma children are looking for refuge – they don’t care where they go, and we will convince the bus driver to go to Kosice.

A couple with Egyptian roots are keen to go Bratislava, but we will offer them accommodation in Nitra. They can’t stop thanking us as they depart.

A lady speaking in broken Czech is trying to provide temporary shelter for nine members of her family sitting in cars nearby.

I hear that some boys from Prešov and Snina are looking for a chair for a disabled person – a young girl with prosthesis up to her hips soon sits with us.

Two teenage girls do not have transport to Brno, they check in at the booth near the Czechs, their friend says something on the phone in Ukrainian, but not a word can be understood amongst the noise.

Six drivers are chaotically offering to pick up passengers, but everyone needs to be checked and double-checked so that refugees are not kidnapped or sold.

I am admiringly watching my Ukrainian friends how they translate their people’s problems for hours and are actively helping to solve them without a break.

Thirteen people in three cars ask for accommodation, they manage to find it at the parish in Snina, through a local charity.

There is a lack of volunteers in this crisis, and Miloš mentions that, by 15:00, it is time to train those taking on the next shift.

We say goodbye and get in the car. We agree that it was not such a difficult day because, in the previous days, there were even more refugees. My shoulders hurt, as are my frozen knees but my back hurts the most. I drive to Košice on autopilot. Throughout the journey, we curse the absence of coordination from the state forces which weakens the effectiveness of the volunteer groups.

We organise the first train to Prague. Some fifty people are pushing for a guide at the last minute, we run to help others with their luggage to make it… One family is no longer lucky and unfortunately the train is literally leaving from under their noses.

A depressed pensioner contacts us with a request that she wants to go to Prague. However, she insists on going by bus, because she tends to feel sick on the train. She has no money and since the buses are not free, she is eventually forced to join the train connection with a transfer through Žilina.

This is just some of what Miloš encountered as a volunteer. He mentions that the majority of people he witnessed were impoverished old women, unhappy mothers and crying children, who thanked Slovaks for their help.

It is a crisis that could do with more hands to help out those in need, as opposed to the war of words that is taking place across the media spectrum.

Volete essere informati delle azioni di DiEM25? Registratevi qui!