This article by Atossa Araxia Abrahamian was originally published in the May 28, 2018, edition of The Nation magazine and is republished with permission.

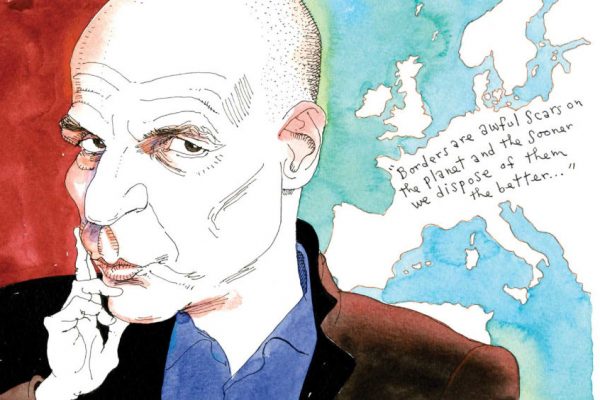

When Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek finance minister who hopes to become the country’s next prime minister in 2019, first came to international prominence in the aftermath of the financial crisis, he was one of those left-wing politicians critical of Europe’s economic institutions, though not necessarily of the idea of Europe itself. Even as a young man, Varoufakis had always been struck by the idea of a united Europe as a way to “forge bonds relying not on kin, language, ethnicity, [or] a common enemy, but on common values and humanist principles.” His brief stint in the Syriza government never shook that conviction, but it did shape his ideas about how Europe should be reformed, and his trilogy of books about the financial crisis—The Global Minotaur; And the Weak Suffer What They Must?; and Adults in the Room—along with his latest book to be released in English, Talking to My Daughter About the Economy, all advance his vision of a more democratic international system.

The problem with Europe is that it is not a political union but a monetary one. Worse, key decisions about spending and lending are shaped by German and French technocrats, not by elected national representatives acting on their constituents’ wishes. Varoufakis’s reform proposals, put forward via his new pan-European movement, DiEM25 (“Day 25” in Latin), are wide-ranging and admirable. He hopes to see something like a United States of Europe emerge out of the EU’s existing structure—one in which Europeans share rights and responsibilities in both good times and bad, aided by the continent’s central banks, which would pool the profits from their various investments in a common depository in order to secure the economy in moments of crisis or scarcity. A share of every initial public offering undertaken in the EU would likewise go toward a universal dividend for all Europeans; citizens would be guaranteed a decent job in their home country, to prevent involuntary migration. By the same token, a common inheritance tax would apply, regardless of where people lived (or died).

“Saving the Sacred Cow” by Atossa Araxia Abrahamian was originally published in the May 28, 2018 edition of The Nation magazine and is republished with permission. Founded by abolitionists in 1865, The Nation has chronicled the breadth and depth of political and cultural life, from the debut of the telegraph to the rise of Twitter, serving as a critical, independent, and progressive voice in American journalism.

Illustration by Joe Ciardiello

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here